阅读:0

听报道

推文人 | 张恩恺

Original article:

Barattieri, Basu and Gottschalk, Some Evidence on the Importance of Sticky Wages (2010),NBER Working Paper No. 16130,Issued in June 2010.

Reference author’s information and Contact:

Enkai Zhang, University of Basel and University of Bern; .

Introduction

Those non-optimizing rational expectations models, especially medium-scale DSGE models will lack the power to make their estimated real effects of monetary policy shocks without assuming the nominal wage rigidities. Reputed macroeconomists like Fisher (1977) and Taylor (1980) followed the steps of Keynes (1936) who assumed the rigid nominal wages to analyze the relationship among monetary policy, employment and output. Erceg, Henderson and Levin (2000) made assumptions of both staggered price and staggered wage contracts a la Calvo when they built up the New Keynesian model. Obviously, we can see the role of the nominal wages’ rigidity as the linchpin of the New Keynesian economic framework, but are there any pieces of evidences? And if it is as important as assumed, how to estimate the rigidity better? This paper, as a combination of labor economics and macroeconomics, gave the solutions and answers by making the best use of the high frequent data offered by Survey of Income and Program Participation(SIPP). One of the main contributions of this paper in assessing wage rigidity is the emphasis on the high frequency of wage adjustment rather than the downward nominal wage rigidity (Kahn, 1997). Moreover, it sheds a light on the application of microdata in those Bayesian tech-based macroeconomic models.

Main method

Under a monopolistically competitive labor market setting, the authors combined the data of hourly earnings and monthly salaries to lower down the statistical measurement error (but, the authors didn’t clarify the way of a combination of those two data with different representative properties). Additionally, with the assumption that non-continuous adjusted wages changed by the discrete amount, the authors used the Bai-Perron-Gottschalk (1998, 2003 and 2005) to test a structural break at all possible dates in a consistent time series. Then they input the micro-data in the Smets and Wouters DSGE model (2008) that used aggregate data to evaluate the importance of the sticky wages.

Main results

1. Greater stickiness

Following the assumption of Blanchard and Kiyatoki(1987) that workers have the ability to set the wage due to the monopolistically competitive supply of differentiated labor services, the authors used the frequency of contractor’s nominal wage changes(rate sheet revisions) to demonstrate the rigidity. Based on the analyzing quarterly frequent interviewed data, the authors found the wage stickiness can be proved greater in their analysis than DSGE models using aggregate US data.

2. Seasonality

To investigate the seasonality, which refers to the pattern of wage adjustment, the authors regressed the probability of wage adjustment for both the reported and adjusted wage series and found the similar result of Olivei and Tenreyro(2008): wage changes more likely in the second half of the year than the first half of the year in the US labor market, but the seasonality are not significant.

3. Heterogeneity

In terms of the wage stickiness among the different industries and occupations, the authors found that services, trade and transport and communication, such kind of jobs without fixed contracts or the wage takers have stronger wage bargaining power (we need to consider the different job market situations in different countries) have the lower level of wage stickiness than manufacturing while construction, mining and agriculture. The other thing we need to note is that those datasets only include the wage information of US citizens and registered immigrants and the authors may neglect the magnitude of illegal immigrants in those low-level blue collar works. Different countries have different labor market, labor protection laws and policies, and labor organizations, which is very important to be considered when we do assume the conditions of wage stickiness.

4. Cyclicality

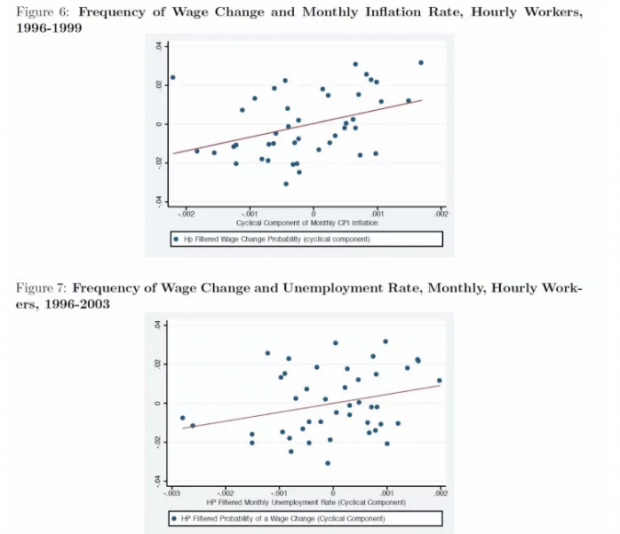

As the figure 6 shows, the monthly inflation rate and the frequency of wage adjustment have a statistically significant positive correlation. Figure 7 shows the positive relationship between the monthly total US unemployment rate and the hp-filtered frequency of wage adjustment. The authors pointed out that Calvo and Taylor models, which are pure time dependent models with nominal wage changes, may not be extensive and those state-dependent wage changes should not be distinguished easily from the time dependent. I suppose state-dependent wage changes make sense because of the differentiated fiscal policies and labor policies in different states, but the monetary policy is basically the same. It would be interesting to think of China’s case, the one-fits-all policies will derive different conclusions, but the hindrances to model will be different for the different fiscal funds in different provinces and autonomous regions (Can we resemble them as the different fiscal policies in different US states? Welcome to contact me to discuss about it).

Notes: I skipped two original results for the repetition of the other results.

Critique

The most stunning point of this AEJ paper is the use of high frequent data rather than the innovation or improvement of the models---the authors may avoid a fact: is it plausible to input the micro data into the models designed to access aggregate data? Should we do some adjustments to make the original models more tailored and convincing? Even the high frequent micro data can be counted as a positive point, one fact we can’t avoid is the period data the authors used belong to one period of a whole business cycle, more frankly speaking, those data may concentrate on the same period and can’t explain the stories of the other economic periods. Apparently, the post-financial crisis economic situation is essentially different from the previous, it will be interesting to input the high frequent micro data across the different economic periods (the summit and the bottom for example) into the DSGE models with the adjustment of conventional monetary policies’ settings into the unconventional.

Abstract

Nominal wage stickiness is an important component of recent medium-scale structural macroeconomic models, but to date there has been little microeconomic evidence supporting the assumption of sluggish nominal wage adjustment. We present evidence on the frequency of nominal wage adjustment using data from the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) for the period 1996-1999. The SIPP provides high-frequency information on wages, employment and demographic characteristics for a large and representative sample of the US population. The main results of the analysis are as follows. 1) After correcting for measurement error, wages appear to be very sticky. In the average quarter, the probability that an individual will experience a nominal wage change is between 5 and 18 percent, depending on the samples and assumptions used. 2) The frequency of wage adjustment does not display significant seasonal patterns. 3) There is little heterogeneity in the frequency of wage adjustment across industries and occupations. 4) The hazard of a nominal wage change first increases and then decreases, with a peak at 12 months. 5) The probability of a wage change is positively correlated with the unemployment rate and with the consumer price inflation rate.

话题:

0

推荐

财新博客版权声明:财新博客所发布文章及图片之版权属博主本人及/或相关权利人所有,未经博主及/或相关权利人单独授权,任何网站、平面媒体不得予以转载。财新网对相关媒体的网站信息内容转载授权并不包括财新博客的文章及图片。博客文章均为作者个人观点,不代表财新网的立场和观点。

京公网安备 11010502034662号

京公网安备 11010502034662号